Newspapers, whether online or in print, have been buzzing the past few days with news about the ‘discovery’ of Nefertiti’s tomb. As even some fellow Egyptologists seem to be eager to welcome and share this, here is my take on the matter.

First of all, we are not talking about a discovery. A discovery would imply that the tomb has actually been found and identified as such. A discovery implies at least some degree of certainty. What we are talking about here, however, is a hypothesis, or rather, a supposition and as long as there are no actual facts to confirm it, that is all it will remain, a supposition.

Studying the high resolution scans that were made of the walls of Tutankhamun’s burial chamber, Dr. Nicolas Reeves noted that there are traces of what could be outlines of doors hidden behind the paintings in two walls. This has led Reeves to believe that there are at least two more rooms in the tomb where Tutankhamun’s burial was found.

Knowing that Tutankhamun died at a young age and somewhat unexpectedly, an equally plausible explanation for the possible presence of two hidden doors, would be that the construction of the tomb was ongoing when the king died, and rather than hurry to complete the additional rooms, they were walled up and hidden behind the paintings of what was to become the king’s burial chamber.

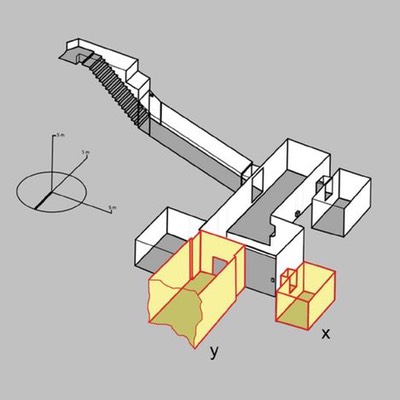

Reeves also points out that the structure of Tutankhamun’s tomb does not follow the typical structure of the tomb of a king, but rather that of a queen.

That Tutankhamun’s tomb does not have a structure similar to that of the kings’ tombs of the period, is more likely the result of this tomb initially not having been intended to receive the king’ s burial, something that has been postulated ever since the tomb was found. It should also be added that Tutankhamun’s reign marked the transition of the Amarna revolution into the counter-revolution era, a time where old traditions where abandoned and picked up again, so what may have been the normal structure of a king’s tomb before the Amarna revolution, may not necessarily have been the norm during the reign of Tutankhamun.

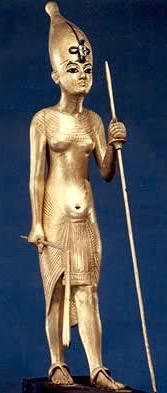

Statue of a king with clear female traits found in the tomb of Tutankhamun.

The next step in Reeves’ hypothesis is the fact that several statues found in Tutankhamun’s tomb, have very distinct feminine traits: breasts and a pot belly. It has already been suggested before that these statues did not belong to Tutankhamun, but to a female member of the royal family. That the person depicted in these statues wears the Red Crown of Lower Egypt or the White Crown of Upper Egypt, both typically crowns that are worn by the king, would suggest that this person was a king. At one point during the Amarna period or just at its end, Egypt may thus have had a female pharaoh!

Assuming this to be the case, it has been proposed, among others by Reeves, that the otherwise elusive Semenekhkare, co-regent during the later years of Akhenaton’s reign and perhaps, for a brief moment, also his successor, may have been this female pharaoh. Against this, it could be noted that there are some reliefs that appear to show Semenekhkare followed by the King’s Wife Meritaton, in a way that strongly suggests that they were husband and wife.

On the other hand, several facts may, according to Reeves, indicate that the female pharaoh Semenekhkare was none other that Nefertiti herself:

- During the reign of Akhenaton, Nefertiti has often been shown in a role that would normally have been reserved for the king only. There are indications that she was the king’s equal, and held kingly powers.

- The prenomen of Semenekhkare was Ankh-kheperu-Re Nefer-neferu-Aten, while Nefertiti’s prenomen -in itself yet another indication that she was considered to be a king- was Ankh(et)-kheperu-Re Nefer-neferu-Aten, the female variant of Semenekhkare’s.

- Semenkhkare makes “his” first appearances at about the same time when Nefertiti seems to disappear.

While there are thus some indications that Akhenaton’s co-regent Semenekhkare may have been a woman, perhaps even Nefertiti, and while it is entirely possible that several of Tutankhamun’s statues found in his tomb, actually belonged to the burial of this female king, their presence in his tomb does not necessarily imply that the entire tomb belonged to here, and even less that she would still be buried in that tomb! It would not be the first nor the last time that a king usurps part of another king’s funerary equipment, or even an entire tomb, for his own burial.

The period following the death of Akhenaton was tumultuous at the very least, with members of the royal family who were initially buried in the Amarna royal necropolis, being moved to the Valley of the Kings on the west bank of Thebes.

Tomb KV55, for instance, was found to contain parts of the funerary equipments of queen Tiyi, the wife of Amenhotep III, but also, of Semenekhkare, including a coffin where the prenomen of the intended owner may have been changed from Ankhet-kheperu-re to Ankh-keperu-re, as well as some funerary tiles that belonged to Akhenaton, while the male skeleton found inside Semenekhkare’s coffin now appears to have been identified as that of Akhenaton.

Is it that surprising, then, that Tutankhamun’s funerary equipment contains objects that were not initially intended for his burial then?

Even though Reeves’ finding that there may possibly be two hidden doorways in Tutankhamun’s burial chamber is definitely interesting enough to be examined further, his conclusion that the tomb also holds the burial of Nefertiti is nothing more than a house of cards, based on one supposition having to prove the next supposition.

Until a way is found to examine what the traces of doorways actually are, and until the Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities agrees to such an examination, Reeves’ conclusion will remain an unproven supposition.

As it turns out, the Ministry of Antiquities is open to have this supposition examined a bit closer.